Prestige: What Hunger Makes of Smoke

The delicate art of being desired

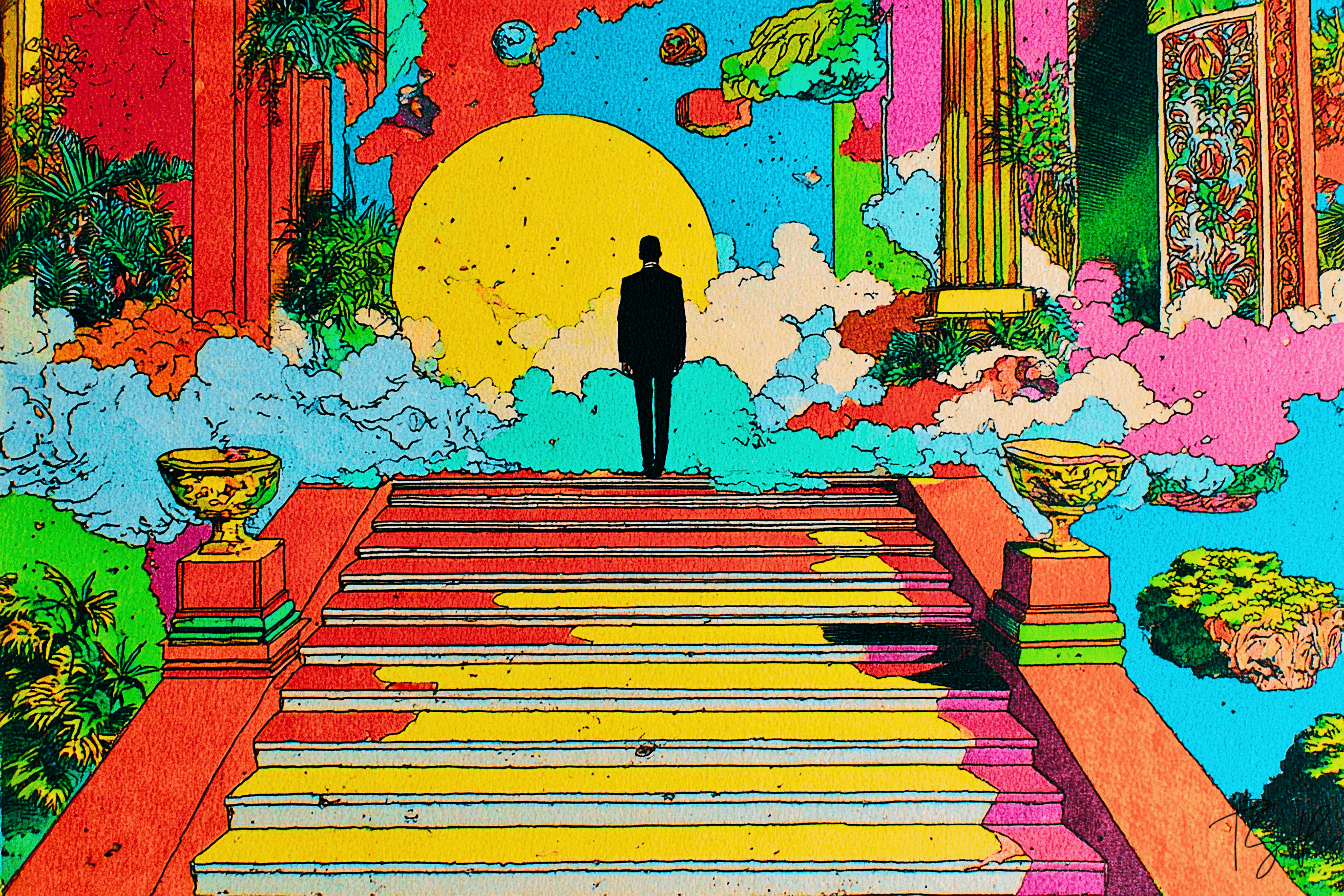

Prestige is a curious thing. It dazzles like stage lights: bright enough to blind us to the wires and mirrors behind the curtain.

Once a word for illusion and trickery, it has since evolved into a symbol of worth and admiration. But beneath its polished surface lies a choreography of perception, power, and desire—one that shapes how we see ourselves and others.

prestige

Etymological Drift

Latin: praestigium—illusion, trick, delusion

French (17th c.): prestige—illusion, enchantment, delusion

English (1650s): prestige—illusion, conjuring trick, deception, imposture

Modern use (19th c. onward): widespread respect or admiration based on achievements or status

The semantic path:

illusion → spectacle → admiration → reputation

Emotional Subtext

Prestige didn’t always mean esteem or excellence. When it entered English in the 1600s, it suggested enchantment—an illusion cast on the senses.

Its Latin ancestor, praestigium, referred to trickery and delusion, especially the kind performed by illusionists. To have prestige was to manipulate appearances—to alter what others saw—not to command admiration through merit.

This early meaning reveals something crucial: prestige was always a performative concept. It didn’t reside in the object itself, but in how it was perceived.

Colonial Power

This idea stuck. Under colonial rule, for example, prestige became a performance—a way for European empires to project authority, especially in places where they lacked real control.

In A Mission to Civilize (1997), Alice Conklin shows how, in French West Africa, spectacle often served as a substitute for governance: medals shimmered on military jackets, governors rode in ceremonial carriages, and neoclassical buildings were erected less for function than for display.

Essentially, grandeur replaced substance.

In British India, prestige was staged just as elaborately. The Delhi Durbar ceremonies—lavish pageants held for royal occasions—were imperial theatre in every sense, projecting supremacy through spectacle.

These highly choreographed events performed power through excess: gold-trimmed processions, elaborate dress codes, and the optics of control.

As Edward Said argues in Orientalism (1979), such displays of visual superiority were central to the colonial project. It wasn’t sufficient to govern; the governed had to believe their rulers were innately refined, destined to lead, and near-divine.

Here, prestige functioned as an institutional illusion. Its purpose was to dazzle, not elevate—a mirage designed to be admired from below.

Exclusivity and Prestige

And that’s the key pivot. Over time, prestige shed its association with trickery and adopted a tone of admiration. But its reliance on perception never disappeared; it still functions by making things look worthy.

Whether it’s a university, a job title, a luxury brand, or an award, prestige tells us something matters, often before we’ve had a chance to ask why.

Naturally, this makes us want to belong—to be seen as valuable. Prestige stirs desire, but also anxiety. If it hinges on perception, it can just as easily be lost, challenged, or revoked. What seems prestigious in one setting may appear hollow in another.

This logic has shaped how we assess universities, governments, and media institutions. Sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called it "symbolic capital"—the idea that something has value simply because others believe that it does. Once that belief becomes socially accepted, it’s hard to question.

But that belief isn’t neutral. Prestige tends to reinforce existing hierarchies of class, race, education, and access. It privileges those already close to institutional power, often sidelining the labour, knowledge, and artistry that exist outside sanctioned spaces.

A "prestigious" institution often draws its power not from what it provides, but from those it excludes. Take Ivy League schools or Oxbridge: their reputations rest as much on selective access as on academic content.

A lesser-known university might offer a curriculum better aligned with a student’s goals, but it’s the perceived prestige that tends to carry weight on a résumé—frequently eclipsing more relevant factors.

The same applies to academia, where citations, credentials, and affiliations shape whose voice is considered credible.

At the same time, prestige carries a certain violence of refinement, so to speak. It smooths over structural inequality with aesthetics. That’s the violence: it makes exclusion look elegant.

As David Graeber writes in The Utopia of Rules (2015), bureaucracy and prestige are often entangled. Systems become so invested in appearances that they reward form over substance, and hierarchy over innovation.

Linguistic Superiority

The same goes for language. In sociolinguistics, linguistic prestige is linked to social power. This means that certain dialects are preferred because institutions endorse them as the norm, not because of their linguistic superiority.

British Received Pronunciation and "neutral" American English are prime examples. Their prestige comes from being modelled by broadcasters, educators, and the elite, not from clarity itself. As Richard Nordquist points out, "words from powerful groups are seen as fancy," and standard—or "correct"—English becomes a proxy for social status.

Rosina Lippi‑Green explores this further in English with an Accent (originally published in 1997), showing how "standard language ideology"—or the belief that a certain accent or way of speaking is the "correct" or "proper" one—is actually based on upper‑middle‑class norms.

This belief unfairly devalues other accents and ways of speaking, turning what should be neutral communication into a marker of credibility.

That’s what makes prestige so emotionally complex. It promises worth but delivers it conditionally. It demands admiration but rarely introspection. And it separates value from visibility, making it difficult to tell when respect is earned and when it’s simply been engineered.

The Power in the Belief

Still, many of us chase it, driven by the desire to be taken seriously. That pursuit is deeply emotional. After all, prestige is about recognition, validation, and the fear of invisibility. So, at its core, it remains a kind of shared performance.

And when prestige fades—when the central belief collapses—it vanishes quickly. That’s the flip side of its allure: it’s as fragile as the illusion it came from. Think of cancel culture, or the wave of toppled statues of leaders who once upheld oppressive systems of power.

Cultural Notes

From Poverty to Prestige: Lobster

Lobster hasn’t always carried the prestige it holds today. Along the northeastern coast of the U.S., it was once so abundant that working-class communities and prisoners commonly feasted on it.

Lobster was reportedly even used as fertiliser by some Indigenous peoples—not because it was undesirable, but because it was ordinary. Maybe even a little monotonous.

Its rebranding as a luxury food began in the 19th century, when advances in rail transport and refrigeration made it possible to serve live lobster inland. There, unfamiliarity bred fascination.

Marketed as exotic and refined, lobster became a delicacy in elite restaurants and luxury trains. And so, its prestige wasn’t innate but constructed through scarcity, distance, and selective exposure.

Prestige, Queerness, and Institutional Tension

Queer thinkers like José Esteban Muñoz warned that chasing prestige inside big institutions—such as universities, mainstream media, or politics—can dilute what makes queer culture truly radical.

In Cruising Utopia (2009), he argues that real queer change isn’t about fitting into these systems or winning their approval. Instead, it’s about imagining and building worlds beyond what those institutions accept or reward.

This creates a delicate trade-off. On the one hand, recognition can bring visibility and resources. On the other hand, it often comes with limits, pushing queer communities to soften or sideline the radical voices that challenge the status quo.

Scholars like Sara Ahmed have pointed out how institutions often only accept queer identities that fit their comfort zones, leaving out more disruptive or complex stories.

We see this tension between institutional prestige and queer radicalism play out in debates over Pride events, queer representation in media, and academic queer studies programmes, where commercialisation can offer visibility but also risk sanitising queer identities.

The result is an ongoing dilemma: queer people want to be seen and taken seriously, but not at the cost of losing what makes their communities unique and transformative.

And so, Muñoz invites us to look past prestige, to imagine queer worlds where transformation isn't measured by prestige but by the capacity to dream and live otherwise.

Subtextual Question

If prestige is a performance, how do we separate genuine admiration from the art of persuasion?