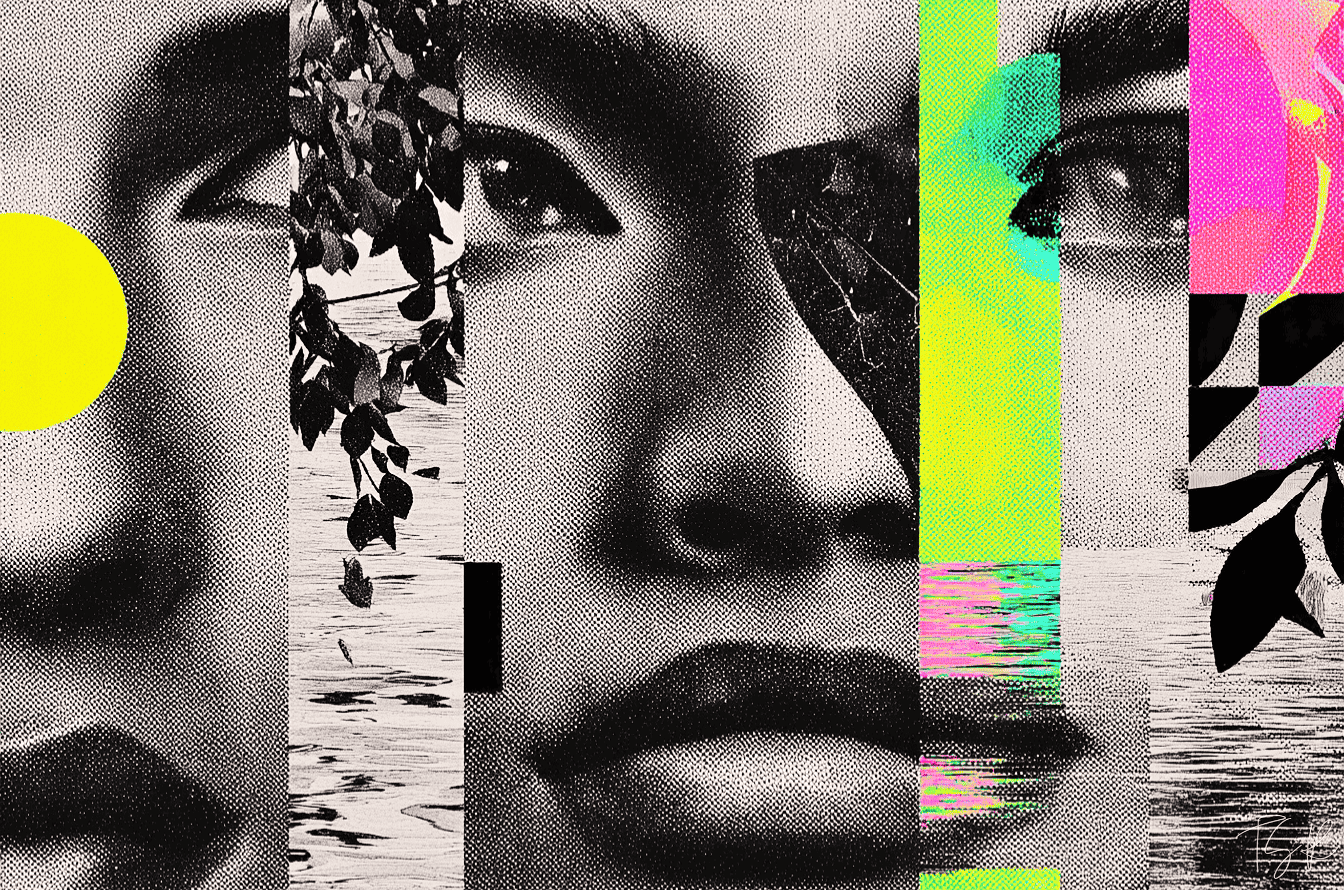

Identity: The Stage and the Cage

From proof to performance, identity has always had an audience

Today, we often think of identity as a deeply personal concept. But historically, it had little to do with inner life, and everything to do with proof.

It served institutions, confirming that someone was indeed who they claimed to be. Over time, the word's definition shifted from external confirmation to internal complexity: identity became something felt, chosen, resisted, and narrated.

identity

Etymological Drift

→ Latin: identitas—sameness, oneness (from idem, meaning the same)

→ Early English use (16th c.): identity as proof of equivalence—being one and the same as something else

→ Modern use: a person’s selfhood, shaped by memory, culture, belief, body, community, and language

The semantic path:

sameness → verification → self-construction

Emotional Subtext

When identity first entered English in the 1500s, it wasn’t about who you were inside, but about proving you were the same person across time and records.

It appeared in legal and administrative contexts, particularly during a period when governments and early modern institutions began formalising population control measures such as census-taking, property registration, and legal contracts.

From around 1538, Thomas Cromwell mandated parish registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials to prevent inheritance disputes and maintain social control. In this context, identity was less about self‑expression and more about administrative order.

Psychological Shifts

But by the late 1800s, the word started to shift. This was partly due to developments in psychology and psychiatry. Thinkers like William James and later Erik Erikson (1960s) began using identity to describe a person's inner sense of self, linking identity development to key adolescent psychosocial stages.

It was no longer about being the same so much as understanding who you were in relation to others.

This was a turning point. Identity became emotional, introspective, and personal. It also became a way of talking about belonging, whether to a culture, class, gender, or nation.

Political Weight

And yet, identity hasn’t always been about the self. Before it became a personal claim, identity was often an imposed label used to sort, exclude, and control. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it shaped borders and belief systems.

National identity helped unite emerging states, while colonial powers used racial and ethnic categories to define who belonged where—and who didn’t belong at all. These identities were assigned and often weaponised, not chosen.

That’s what makes the subsequent shift so emotionally charged. By the mid-20th century, identity began to shift from something done to people to something people could do for themselves.

Especially during post-WWII decolonisation and the American civil rights movement, identity gained political weight. Marginalised groups started using the word to assert visibility: Black identity, gay identity, national identity. Instead of categories, these were claims to history, rights, and agency.

Fluidity

From the late 20th century onwards, post-structuralist and queer theorists started questioning whether identity was ever stable at all. Writers like Judith Butler and Stuart Hall argued that identity isn’t something we are, but something we perform or negotiate, depending on the context.

This helped shift the understanding of gender, sexuality, and race from fixed traits to lived experiences—shaped by power, history, and language.

In contemporary use, identity certainly carries a lot of tension. It speaks to a desire to be known, but also to the fact that being known can be dangerous, or near impossible.

And so, in queer, diasporic, or racialised contexts, identity is often built around negotiation rather than stability: a composite shaped as much by friction as by choice.

Uncertainty

This shift from sameness to self-definition also brings uncertainty. Identity is no longer fixed or easily understood, but something fluid. That uncertainty is part of its power, but also what makes it threatening to systems built on control and exclusion.

And while what began as a tool for sameness has become a way to express difference, the original function of the word hasn’t fully disappeared.

In legal systems, passports, databases, and surveillance technologies, identity still means proof. We continue to live with the tension of a word that tries to do both: describe the ever-changing while conforming to a rigid system.

Residual Meaning Rating

★★★☆☆ (3/5)

The idea of sameness persists, especially in bureaucratic settings. Identity is still very much something to be verified, matched, or filed.

But in personal and cultural contexts, the word has moved beyond its origins. Its emotional weight now lies in difference, not sameness. Above all, it presents selfhood as something defined from the inside out.

Cultural Notes

Identity crisis and modern instability

Term coined by psychologist Erik Erikson (1950s)

Described the loss of self when traditional anchors (religion, family, nation) stop offering direction

Marked a shift towards identity as something constructed, not inherited

The state’s grip: fixed identity in a fluid world

Bureaucratic systems still require identity to be consistent

Passports, census forms, biometric IDs, and medical records demand sameness

Despite shifting cultural understandings, the state flattens nature's complexity to maintain control

Theory and resistance: identity as performance or negotiation

Judith Butler (1990): gender identity as something performative, produced through repeated acts

Stuart Hall (1996): cultural identity as something relational and fragmented—shaped by memory, language, and absence

For the marginalised, identity isn't a given but something constantly remade

Language and emotional range

In Polish, tożsamość ties closely to sameness, and it's often legal or academic in tone

In English, identity stretches to carry emotional, political, and personal weight

Modern resonance: identity as claim and constraint

A staple in activism, branding, and everyday speech

Can signal pride, protest, or belonging

But also risks essentialism and over-categorisation, fixing what should remain fluid

Subtextual Question

Can a word built on sameness ever fully contain the multiplicity of the self?