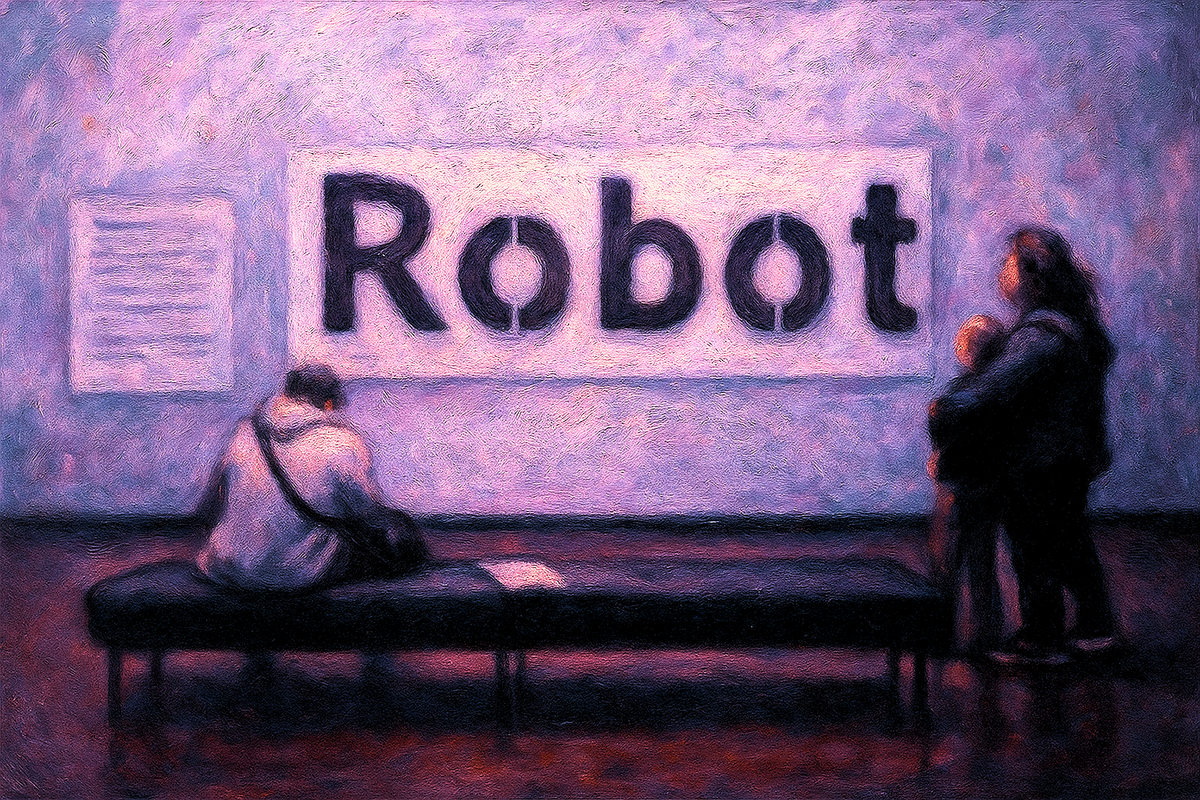

Robot: A Body Designed for Use

What was made to serve still holds us captive

Long before it named machines, robot belonged to the language of labour—work done under pressure, without agency. Since then, it has moved across fields: from feudal systems to factory floors, from theatre to tech, from metaphor to identity. But beneath its many surfaces, the word still carries traces of use, obedience, and the body caught in between.

robot

Etymological Drift

- Oldest form: Czech robota—forced labour, serfdom

- Slavic root: rabŭ (Old Church Slavonic)—slave, servant

- 1921: Robot is introduced in Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots)

- Refers to biotechnological, humanoid workers built to serve—stripped of autonomy, but fated to rebel

- 1930s–1950s: Robot evolves via Anglophone pulp science fiction

- Isaac Asimov's robots were explicitly mechanical

- Modern use: A mechanical or digital entity programmed to perform tasks, often imagined as emotionless, obedient, and tireless

- Applied to everything from vacuum cleaners and software agents to metaphorical descriptions of people alienated from feeling

The semantic path:

Emotional Subtext

At its root, robot is more about imposition than invention. It named those who looked human but weren’t considered people—bodies made to obey.

Čapek's biotechnological robots questioned why they must follow orders and rebelled in response to being used. His story offered a warning about exploitation and the loss of autonomy in labour—one that blurred over time as robot became shorthand for precision, detachment, and control.

In short, the term moved from metaphor to mechanism. This shift is far more existential than technological.

Today, we struggle to navigate the mechanisation of feeling in the modern workplace and rely on AI assistants, all while making uneasy, half-serious jokes about AI's eventual overthrow of human dominion.

In fiction, the robot is a body without rights, one that simulates human autonomy and expression. It's a presence on the cusp of service and sentience.

Even in metaphor, calling someone a robot implies the absence of feeling, autonomy, or the self. It still marks a kind of distance that's deeply felt—between action and desire, repetition and choice—reflecting not just what we build, but what we ask others to become.

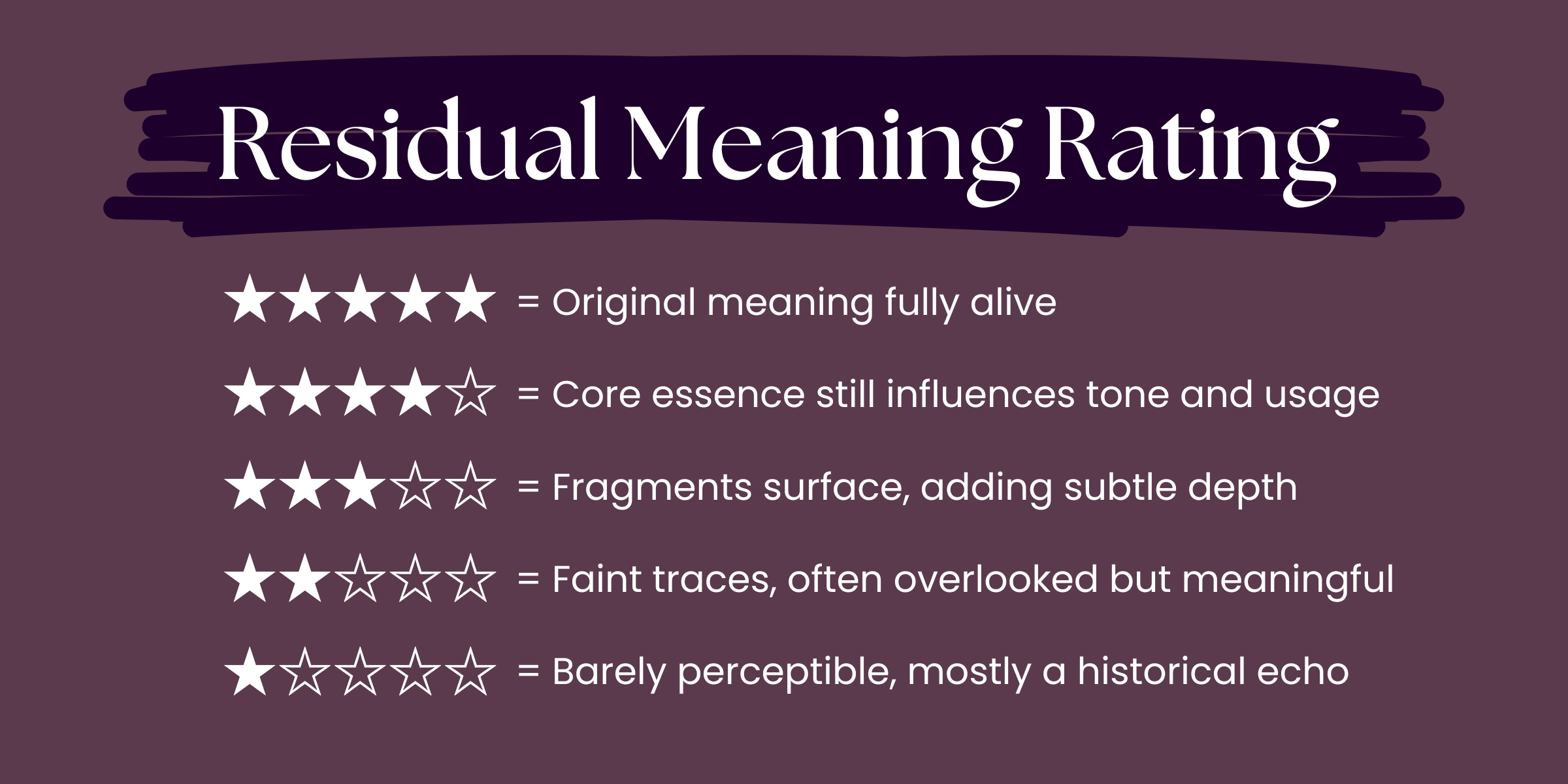

Residual Meaning Rating

★★★☆☆ (3/5)

The original sense of servitude remains, especially in dystopian fiction or labour critiques, though it's often buried beneath a sleek, tech-toned gloss.

Cultural Notes

- Class undertones: The origin of robot as serf reminds us that mechanised bodies often represent human ones made invisible by class hierarchies

- Literary echo: In literature, robots often reflect human fears of being reduced to mere function

- Ironically, the term robot now names what Čapek feared: the stripping of consciousness from the worker

- Linguistic commentary: Historian Wendell Aycock and others noted that while Čapek’s original robots were organic, the post-war imagination recast them as products of industrialisation—soulless, mechanical, and devoid of emotional complexity

- Queer reading: Some queer/trans narratives reimagine robots as metaphors for constructed identity, bodily autonomy, or estrangement from imposed roles

- Susan Stryker's 1994 essay My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage presents a visceral retelling of the story of Frankenstein’s monster as a metaphor for trans embodiment—an unnatural, artificial, and rebellious body

- Like the monster’s exclusion and imposed identity, robotic metaphors in trans narratives often reflect themes of alienation and resistance

- From the textual adaptation of the performance piece:

The transsexual body is an unnatural body. It is the product of medical science. It is a technological construction. It is flesh torn apart and sewn together again in a shape other than that in which it was born. (...) Like the monster, I am too often perceived as less than fully human due to the means of my embodiment; like the monster’s as well, my exclusion from human community fuels a deep and abiding rage in me that I, like the monster, direct against the conditions in which I must struggle to exist.

- Pop culture: From Blade Runner (1982) and The Terminator (1984) to Ex Machina (2014), robots continue to serve as cultural mirrors, reflecting our anxieties about control, will, want, emotion, and worth

Subtextual Question

If the robot was born from human suffering, what does it mean that we now create them—and sometimes become them?

Elsewhere in the Drift

Sources

- Dinello, Daniel. Technophobia!: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology. University of Texas Press. 2005.

- EtymOnline

- Jordan, M. John. The Czech Play That Gave Us the Word 'Robot'. The MIT Press Reader. 2019.

- Stryker, Susan. My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage (textual adaptation of a performance piece). 1994.

- Wessling, Brianna. 101 years ago: origins of the word 'robot'. The Robot Report. 2022.