Muscle: Where the Animal Went

A story of instinct, control, and what the body leaves behind

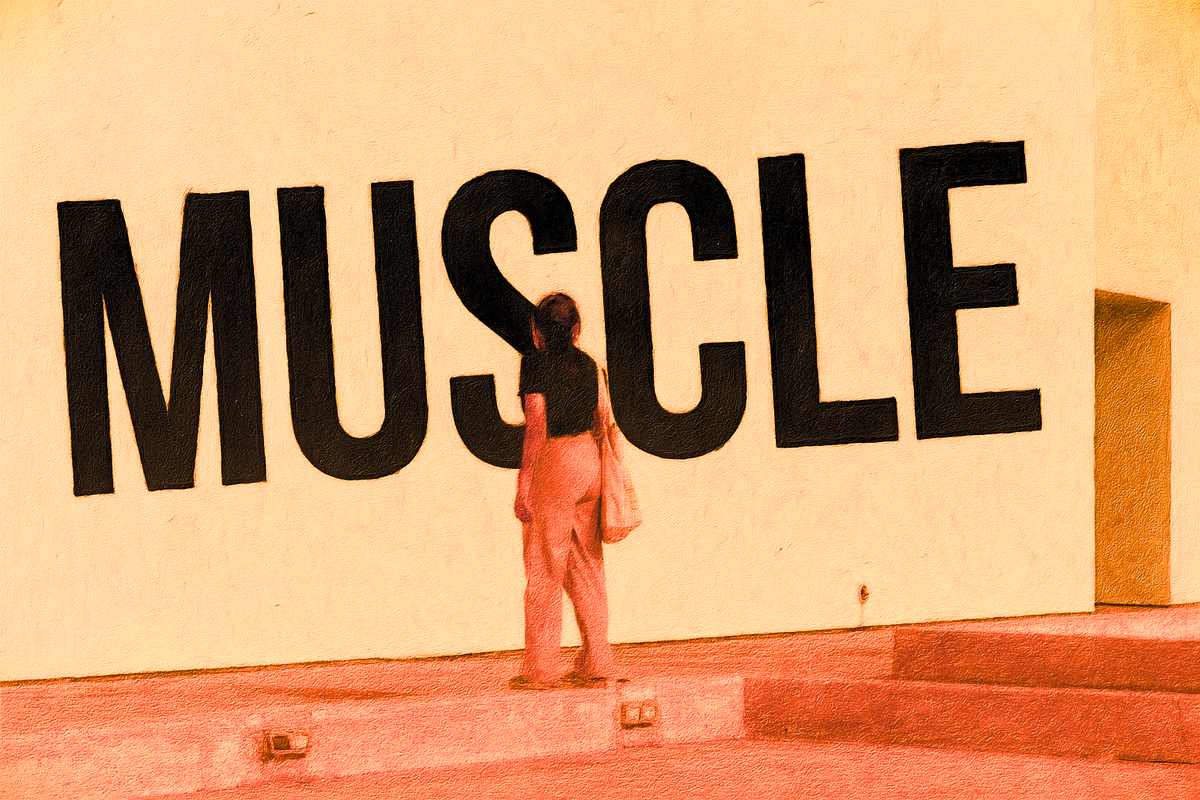

Before it became a marker of strength, muscle was a word for something small and restless—a twitch beneath the skin, a "little mouse" moving beyond control. Over time, the word flexed and hardened, fitting itself to new ideas about power, attraction, and the performance of being.

muscle

Etymological Drift

- Oldest form: Latin mūsculus—"little mouse" (diminutive of mūs, meaning "mouse")

- Visual metaphor: the ancients saw the play of muscle under the skin as reminiscent of a mouse scurrying just beneath the surface

- Middle French: muscle—adopted into Middle English (14th century)

- Shift from visual metaphor to anatomical term: the biological tissue that contracts and creates movement

- 16th–17th centuries: Anatomical term solidifies in English medical texts

- Muscle becomes the default term for contractile tissue, losing the playful, visual association with mice

- 18th-20th centuries: The industrial age reframes muscle as a mechanical force

- As industrial metaphors take hold, muscle enters the language of labour, strength, power, and force

- By the 20th century, muscle morphs into something performative: bodybuilding, masculinity, political strength (something to display and measure)

- Modern use: Muscle is as much about metaphor as it is about tissue ("political muscle," "muscle through," "muscle memory")

The semantic path:

Emotional Subtext

The history of muscle is a slow shedding of vulnerability. Its drift says as much about language as it does about how we frame the body.

The early metaphor—something small and restless—humanised the body. It was visual, tactile, and oddly affectionate. A word for something involuntary, observed, and external to human control.

Over time, industrialisation, body culture, and shifting ideals of masculinity reframed muscle as an external display. The body became spectacle, with the word turning into a status marker, a visual shorthand for power and dominance.

Like many words reshaped by capitalism, muscle now lives inside performance culture. It belongs to gyms, politics, and ambition. It’s both aspiration and anxiety. Choice and cultivation. Something you build. Something you own.

What was lost was the intimacy of observation—the sense of bodily strangeness, the metaphor of animal kinship. Flesh as something alive, mobile, and precariously small.

This loss takes on particular weight when we consider trans and gender non-conforming bodies, for whom muscle occupies a complicated emotional space, one that can mean both dysphoria and agency.

For some, building muscle is a reclaiming of physical identity, a way to sculpt visibility in line with self-perception and desire. For others, it’s a source of alienation: a biological inheritance that doesn’t align with how the body is experienced.

There’s an irony here that sits deep under the skin: the semantic move from reaction to control, instinct to will. The word’s journey runs parallel to broader cultural shifts: the rejection of softness, the commodification of the body, the demand for visible proof of effort and desirability.

The cultural script around muscle—as a visible, measurable signifier of masculinity—leaves little room for nuance. But while it's become the measure of strength and desire, its linguistic DNA remains restless.

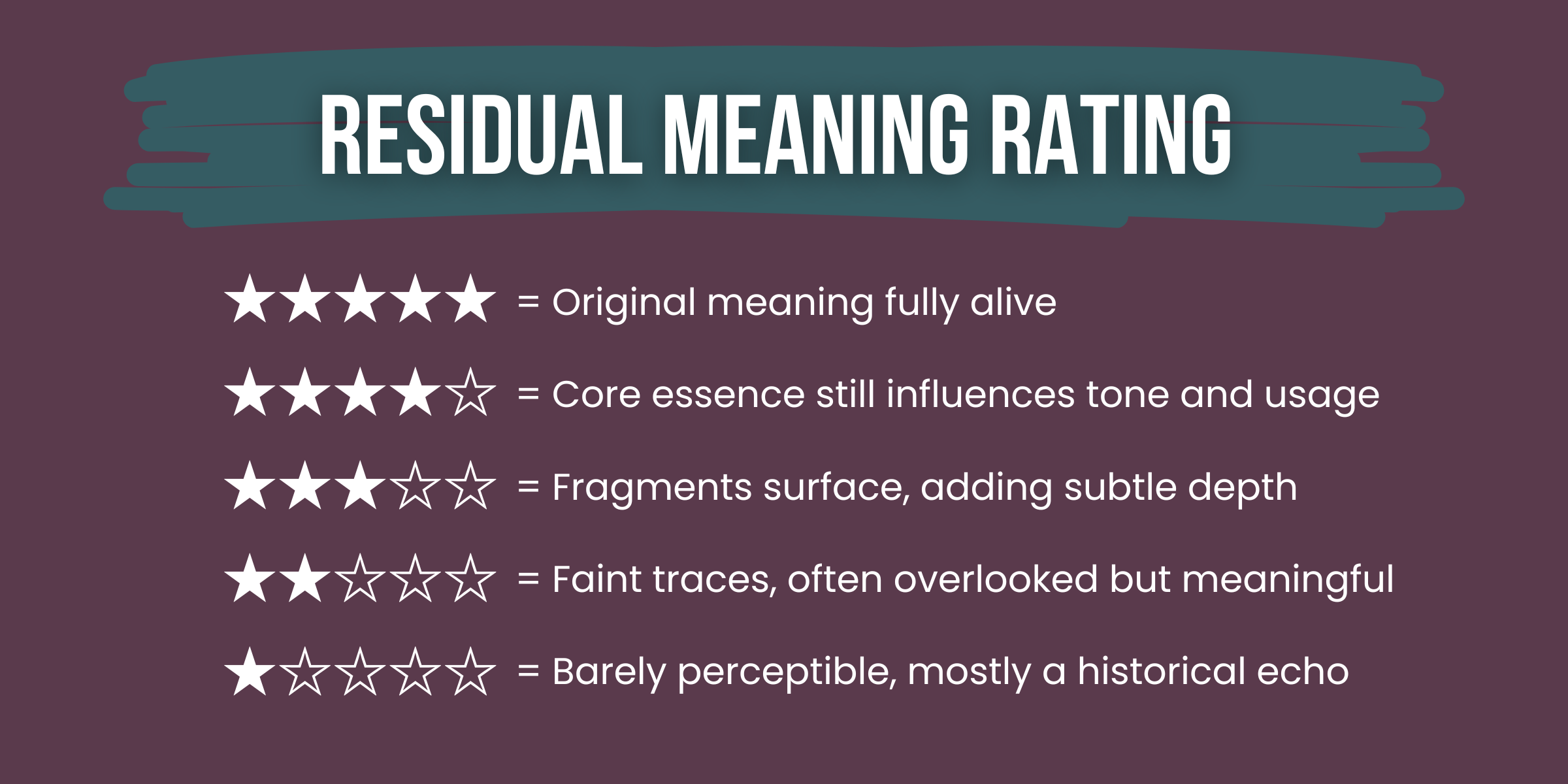

Residual Meaning Rating

★★☆☆☆ (2/5)

You might not hear the mouse in casual conversation, but you’ll still feel it in the tremor before you lift, or the shake before you steady.

Cultural Notes

- Gender and power: Muscle carries strong gender associations in pop culture—usually linked to masculinity, physical strength, and dominance—even though its roots aren't tied to any one gender

- The fitness industry markets “lean muscle” or “mass gains,” reinforcing binary expectations

- For queer and non-binary people, navigating this language often means reclaiming, reshaping, or outright rejecting the cultural script

- Class associations and control: The phrase “muscle for hire” reflects how working-class bodies became tools of labour for other people's agendas (dockworkers, security, strike-breakers)

- For much of history, muscle was tied to labourers—people whose bodies had to work to survive

- Politically, “flexing muscle” refers to wielding influence, but the metaphor is still rooted in bodies put to work

- Performance and aesthetics: With the rise of gym culture, the body’s labour shifted from survival to spectacle—sculpted for appearance rather than necessity

- Violence and coercion: Muscle also lives in the language of force: “muscle someone out,” “put some muscle behind it,” “strong-arm tactics”

- The shift from involuntary twitch to deliberate aggression reveals how language absorbs power dynamics—and a charged desire for dominance

Subtextual Question

What would strength feel like if we still thought of it as something small, nervous, and always on the edge of flight?

Elsewhere in the Drift

Sources

- Bordo, Susan. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body. University of California Press. 2003.

- EtymOnline

- Klein, Alan M. Little Big Men: Bodybuilding Subculture and Gender Construction. SUNY Press. 1993.

- Merriam-Webster

- National Geographic

- Prosser, Jay. Second Skins: The Body Narratives of Transsexuality. Columbia University Press. 1998.

- Thompson, E.P. The Making of the English Working Class. Vintage. 1966.