A Soft Bite: The Sweet Weaponry of Language

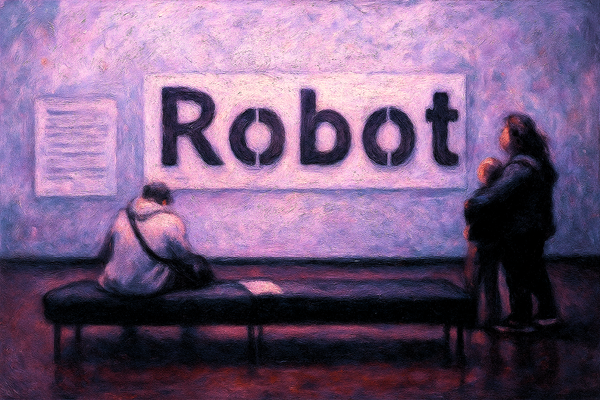

When language smiles, look for the teeth

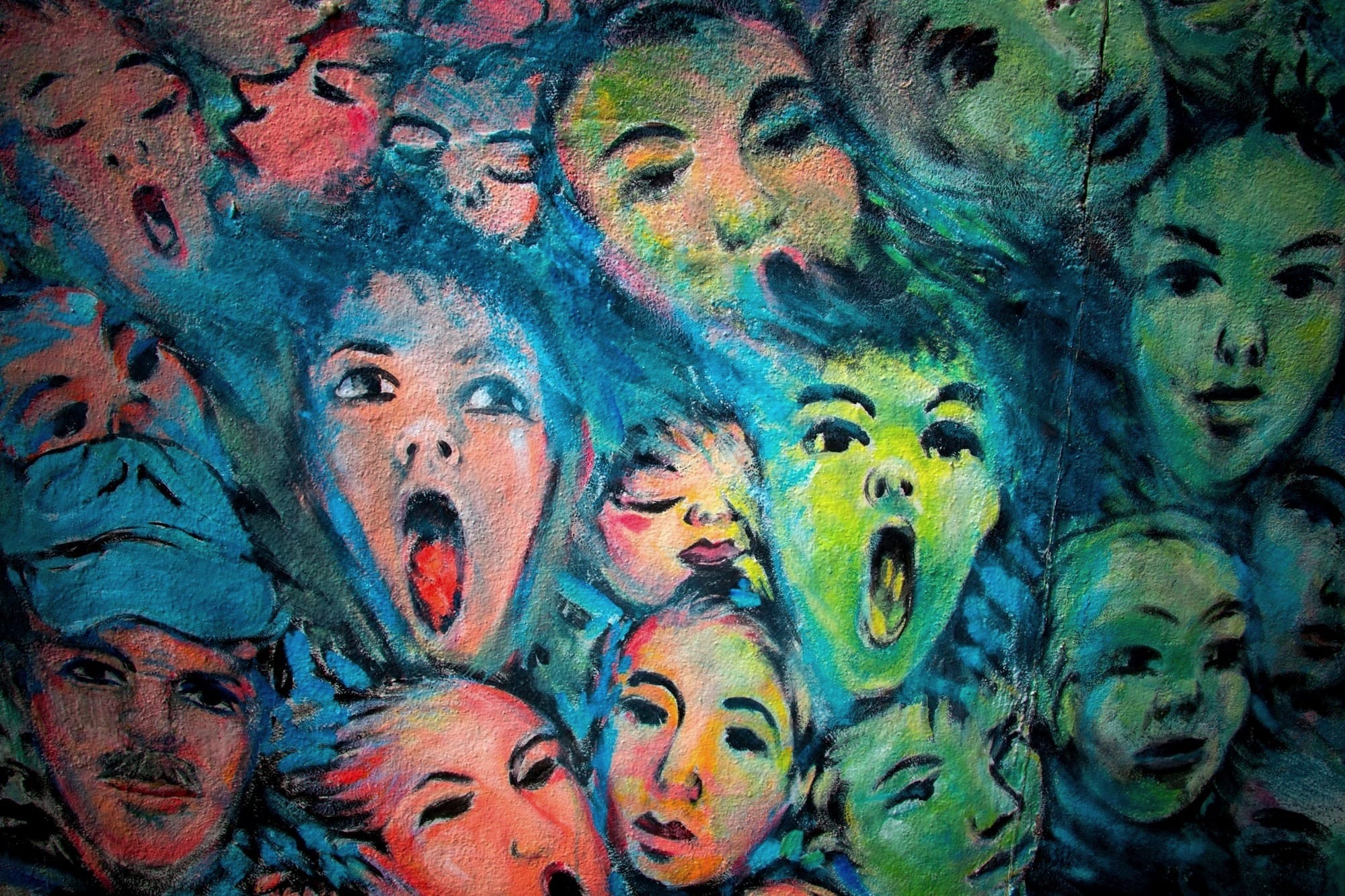

Can language ever be truly neutral? It's true that some words feel lighter than they really are. Fruity. Delulu. They land with a grin—playful, unserious, not meant to be taken too seriously. But their ease is often misleading.

Diminutives tend to disarm. They shrink the serious into something manageable. A little absurd, a little sweet—just enough to laugh off.

They’re often used affectionately, sometimes self-referentially, but that doesn’t necessarily make them neutral. In fact, that’s what gives them both their power and slipperiness.

These words may seem small, but they carry weight. Not because they’re cruel, exactly, but because they’re casual. And in that casualness, they cross boundaries they pretend not to see.

Let's explore what happens when language softens the edges of identity, desire, and expression—not to protect, but to contain. When words that seem to dim actually illuminate power, performance, and perception in ways we rarely stop to notice.

The Comfort of Smallness

Linguistically, diminutives shrink things. They're meant to signal playfulness, affection, or harmlessness. Think of "cutie" and "bestie."

But that smallness can also infantilise, trivialise, or defuse seriousness. In cultural discourse, it turns certain identities or behaviours into jokes, rendering them soft targets for mockery.

Take "fruity," for example. Though playful on the surface, it still carries an undercurrent of otherness, wrongness, and subtle mockery—echoing the historical use of "confirmed bachelor" as a way to sidestep the discomfort of queerness.

Similarly, "touched," once used to describe those suffering from mental illness, distills a complex and painful reality into something dismissively palatable.

And let’s not forget "delicate condition," the euphemism for pregnancy that not only softened the conversation about women's sex lives but also tucked it away in a quiet corner, never to be discussed openly.

The danger of "cutesifying" real pain, real difference, is that it allows systems of exclusion and mockery to persist invisibly.

Fruity, Delulu, and the Art of Reclaiming Language

Fruity

In slang, "fruit" was originally a slur for queer men, a subtle way to describe someone whose mannerisms were seen as effeminate or flamboyant.

In the early 20th century, especially in Western societies, words like "fruity" became a coded term within the LGBTQ+ community, offering a kind of linguistic camouflage in an era of rampant homophobia.

Over time, it was adopted more playfully—particularly in LGBTQ+ spaces—as a tongue-in-cheek self-reference, a way of laughing at the world’s discomfort with gender nonconformity.

But even as the term became a playful badge of identity, its history still carries an undertone of condescension, particularly when used by those outside of LGBTQ+ circles.

At its core, "fruity" serves as a euphemism for non-normative identities, making queerness palatable by rendering it digestible—a form of queerness made consumable. It’s affectionate irony layered over a deeper, often patronising discomfort.

Delulu

This term, a shortened version of "delusional," has a more contemporary evolution. "Delulu" was originally a self-deprecating term used by K-pop fans, often women or queer people, to describe unrealistic romantic or aspirational fantasies.

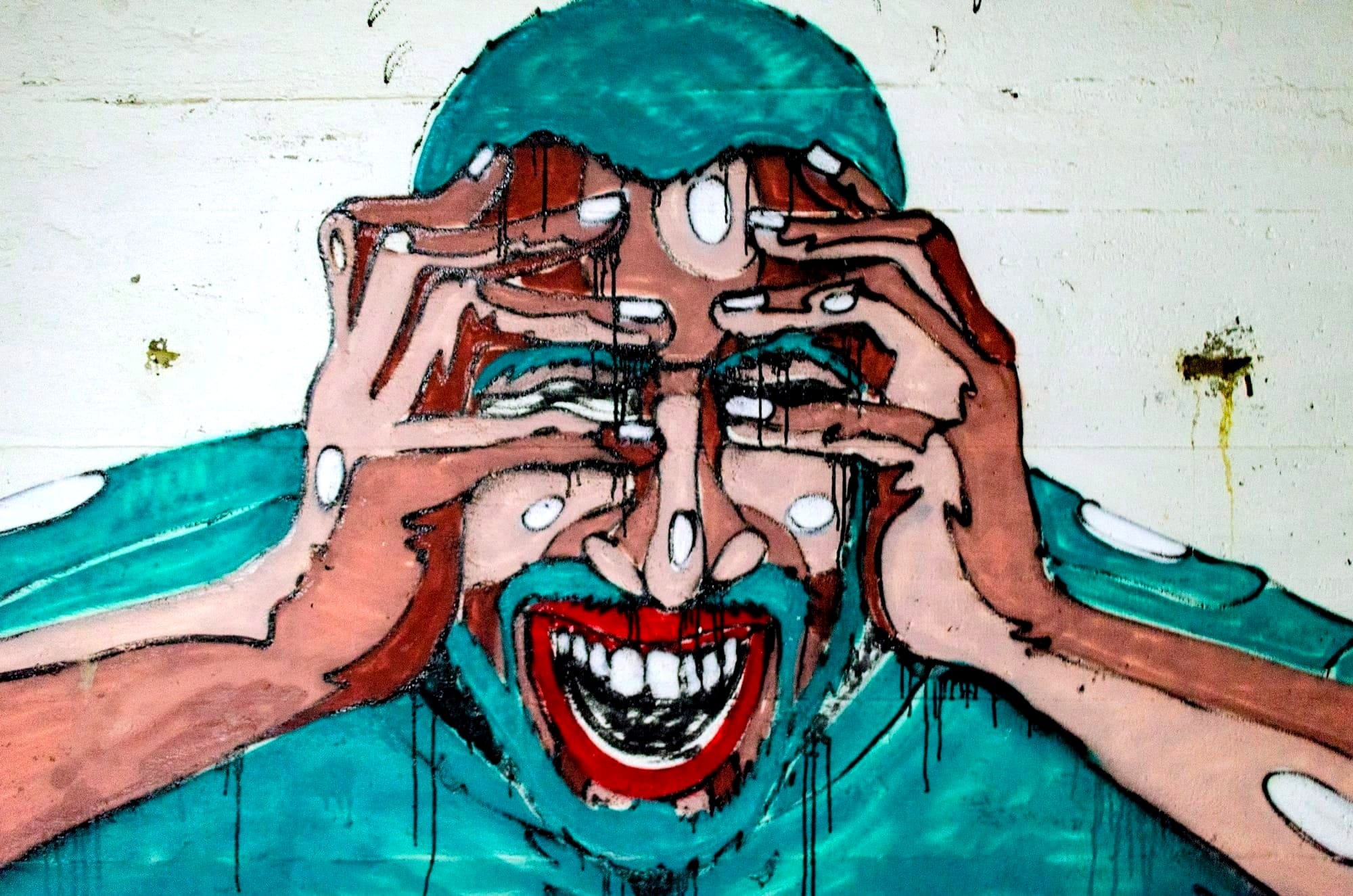

Historically, non-heteronormative expressions of love and identity have been labelled as deviant or delusional. And so, much like women's emotions, pathologised through words like "hysterical," queer individuals have faced the invalidation of their desires.

The use of "delulu" both reflects and critiques this history: starting as self-aware irony, it ultimately reduces valid aspirations to a quirky flaw.

As the term gains traction in online spaces, it highlights how fandoms and subcultures navigate self-expression. While reclaiming a negative label, it also shows how even the most self-aware efforts to reclaim can still carry the weight of historical baggage.

"Softness" that Masks

Cringe

Originally used to describe physical discomfort, “cringe” has evolved into a quick way to dismiss vulnerability or earnestness. It’s a term that shrinks genuine expression into something awkward and easy to laugh off.

Pickme

"Pickme" refers to women who adopt traditionally patriarchal behaviours to earn male approval. Over time, it’s morphed into an online meme that turns a complex cultural critique into a simple, dismissive label.

Historically, women have been conditioned to compete for male attention, a practice rooted in centuries of gender inequality.

And yet, “pickme” flattens this complicated negotiation of identity and survival into a viral concept. Its popularity in meme culture strips the nuanced challenges of internalised misogyny, turning them into something to laugh at instead of unpacking.

Extra

When “extra” is thrown around, it’s used to label intense emotion or effort as laughable or excessive. It’s a subtle way to shame expressions of emotion and identity, especially among women and queer people.

The term is tied to femmephobia, which is the devaluation and policing of femininity across all genders. It reflects a bias against people who display traits stereotypically coded as feminine—expressiveness, emotion, flamboyance—regardless of their gender identity.

Special

"Special" has long been a euphemism for individuals with disabilities, softening social discomfort while maintaining distance and otherness.

The National Education Association (NEA) points out that terms like "special needs" can subtly reinforce the idea that being disabled is something to be ashamed of, urging a move towards more direct language like "disabled" and "disability."

Peculiar/Eccentric

"Peculiar" and "eccentric" were historically used to describe people who didn’t conform, including neurodivergent, queer, or culturally "other" individuals.

While they might have seemed gentler, these terms still kept a safe distance from the perceived threat these individuals posed to a rigid, conventional society.

And so, these words reveal how language can be weaponised to marginalise anyone who challenges social norms—whether through identity, behaviour, or ways of thinking.

Conclusion

The words we use—whether playful or dismissive, affectionate or derogatory—carry the weight of history and power. They shape how we perceive others, and in turn, how society structures itself.

As we've seen with terms like "cringe," "extra," or "peculiar," language often acts as a tool to label and marginalise, disguising deeper social biases under the guise of humour or casual critique.

While some of these terms have evolved or been reclaimed by subcultures, their histories remind us that language is never neutral. It's a reflection of the values, prejudices, and power dynamics that define a culture.

As we continue to navigate complex identities and experiences, it’s crucial to be mindful of how language can both reinforce and challenge social norms.